In the last blog I talked about musical figures such as motifs, melodies, rhythm patterns, figurations, harmonic sequences, etc. Being actors in musical stories they can be positioned and repositioned differently in the musical space and time, they can move away from each other, approach and overlap. Some of them can act sharp in the foreground, the others get blurred in the background; they can be painted in different colors, appear deformed, distorted and almost unrecognizable.

Generalizing, we can say there is a whole range of composing techniques, in which not the object itself but our view on it is changed. In other art forms like painting, sculpture or literature these techniques are called perspective.

These striking parallels between music and other arts in regard of positioning the represented objects make also remember that the activity itself of “composing” is an allusion to the Latin “componere” meaning “put together”. Not surprisingly, the word “perspective” proves to be very helpful when talking about music and it allows us a deeper understanding of the “composer’s kitchen”.

For those of you who are on friendly terms with math, you may know there are two main ways of looking at a composition: the describing the functions of the components or visually representing the objects from different sides. The first type is practiced in algebra, the second in geometry.

Before it gets too complicated, let us turn back to arts where these two kinds of approach correspond to system or accordingly to perspective analysis. The last is called narratology in literature. There seems to be no suitable word in the musicology till now, so I will just use the most compatible word “perspective”.

A complete systematic description of the perspective situations available to a composer would be ripe for a dissertation, so I will sketch the most important ones.

*****

Narrative mode – there is a big choice starting with a solo up to a large symphony orchestra with choir. All intermediate forms like a duo, trio, quartet, quintet, etc. are possible. Also mixed forms with a constantly changing narrator are possible, for example a concerto, where a soloist is competing with an orchestra. If there are more soloists it is called concerto grosso.

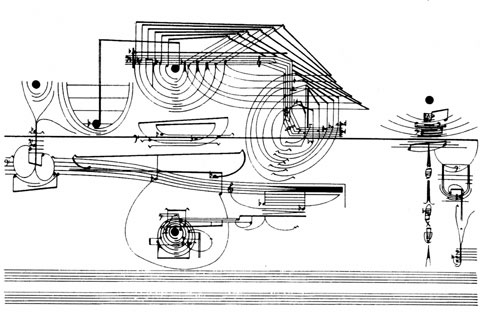

Let us take a look at the literature. We can have a subjective or omniscient view comparable with solo vs. any kind of ensemble, alternating narrators are also possible. In painting the first-person perspective outweighs but also multiple perspectives are possible, they could be positioned beside each other in streaks or concentric circles like in some icons, or overlap as for example in some pictures of Piccasso.

Vertical – the register of a musical figure: central, high, low, or mixed. We know it from the music theory as transposition. A special case is also known as the polyphonic technique of inversion, in which the original melodic structure is vertically inverted so that the highest tones become the lowest and vice versa.

The initial high strings of Wagner’s opera “Lohengrin” is a good example of the so-called bird’s eye view when the action is viewed from “above”. In contrast, the beginning of the second movement of the 2nd Sonata (B-minor) by Chopin, the funeral march, gives us a good look at the main motif “from below”, so to say, seen from the Inferno. You can imagine that the possibilities are inexhaustible.

Horizontal – a musical figure has its tonal and rhythmic sides, which I would like to compare with the frontal and side views. If both tonal and rhythmical axes are elaborated and complex, we can speak of a central perspective.

Sometimes composers vary a motif taking just its melodic or rhythmic part. In these cases we would speak about frontal or side view. A good example would be the first movement of the fifth symphony of Beethoven, where the famous “fate motif” varies in the development falling apart alternatively to a sequence of pitches or to a rhythm figure.

In general, more complex rhythms define more spatial depth of a musical figure showing it with more details.

Distance – it plays a very big role in the music and is usually defined by the volume. Put simply: louder=near vs. softer=farther. More playing instruments also signifies more details, which suites perfectly the concept of distance, especially when we deal with thirds, sixths, or more complex harmonic doublings.

In “Bolero” by Ravel we can virtually feel the music approaching. The ever-increasing volume and the growing number of instruments and doublings evoke the distance change from “far” to “right in the middle “.

Focus – from a clear melody to a “blurred” figuration anything is possible in the presentation of musical figures. The sharpness of the foreground is often emphasized by special accents and staccato articulation. Short tones with distinctive rhythms suggest an almost photographically working sharpness, whereas smooth legato arpeggio figurations give the impression of vagueness out of focus.

Some Preludes of Debussy, like “Ce qu’a vu le vent d’ouest” (What the West Wind Saw), for example, are full of “blurred” figurations that are supposed to picture the contourless wind; otherwise, his “Claire de la lune” has a clear distinctive melody surrounded by indistinct figurations.

Color – additionally to the number of instruments in a composition, their choice is also important: a duo of two violins presents a totally different perspective compared to, let us say, a violin and a trumpet. Depending on the composition, it can also have a special meaning in the musical story. From optics we know the effect of the warmer (reddish) colors of the objects giving the impression of being nearer and of the colder (bluish) colors as being farther.

This effect is also known in music where string instruments, with richer overtones, sound “warm”, “intimate” and “close” whereas woodwinds seem normally to sound more distant, especially when played without the “warming up” vibrato. The normal positioning of the orchestra instruments on the stage amplifies this effect, as the wind instrument players sit behind the strings.

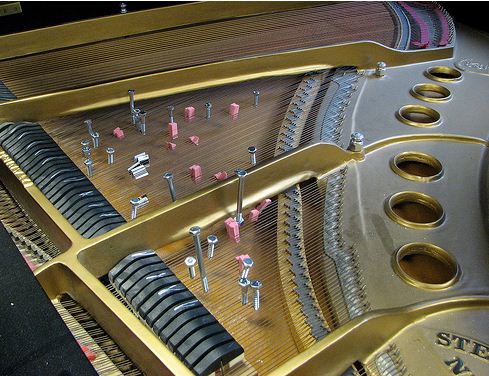

A special case is the timbre of the piano, which basically sounds quite neutral in color, due to the lack of vibrato technique! Thus, it is similar to a black and white picture. I hope the pianists won’t get angry with me because of this comparison – it doesn’t minimize the ability of the piano sound to evoke strong emotions! 🙂

Time – as also the musical space, it allows many modifications of the perspective: it can be stretched and compressed, accelerated and slowed down. Apart from changes of the main tempo, individual figures can be varied rhythmically and run, for example, in half or double rhythmic values. Of course, it is just the simplest possibility.

In extreme cases, such as the renaissance motet, Gregorian chants were stretched so far that its single notes became extremely long bass tones and served as the base for whole episodes. Such tones were eventually stretched to several minutes!

Style – a relatively new type of perspective change is the stylistic axis: traditional versus modern, which means that one and the same figure can be for “disguised”, for example, in Baroque, Classical or Romantic.

Already in the renaissance parody mass quotations from other styles were a commonplace. Often they changed the view on the underlying cantus firmus representing it from different perspectives.

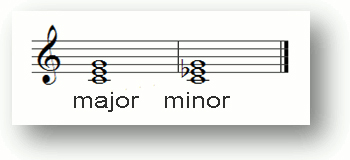

One of the most famous examples of this technique is very common in Schubert’s music. The composer “dresses up” his tunes alternatively in major or minor keys. In the western classical tradition major is considered to be “clearer” and “more stable”, in other words it was regarded as the genuine “original”. Minor, however, emerged as a deviation, symbolizing “pathological” phenomena such as sadness – the greatest sin in Christianity. In Schubert’s music this meaning is getting lost but the time perspective remains.

In the music of the last decades the third movement of Berio’s “Sinfonia” would be an excellent example of the stylistic dressing up. Here the original music from the second symphony Mahler is overlied by diverse quotations and stylistic imitations. At some points we are able to recognize the music of Mahler but some of them sound like a strange disguise of the original quotation.

*****

All these perspective settings do not stay the same during a composition and the changes from a setting to setting allow many possibilities: from sliding or gradual panoramic change to clear cuts – everything is possible. The composer is free to form them and to make them interesting and diversified, so that it doesn’t get boring for the listener.

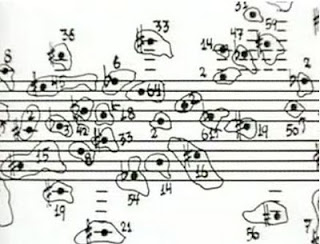

The two extreme settings would be the so-called “”minimal music where the perspective is close to absolute static and the changes are extremely reduced. On the other hand we have the so called “new complexity” with rapid and continuous changes of perspective, so that the listener is no more capable of tracing them.

A balanced out but rich on variations perspective is a premise for a successful communication with the listener whose capacity shouldn’t be underestimated but also not overused. The numerous masterpieces of music history are the best examples and a good point to start.

I hope this short sketch of musical perspective will give some inspiration to an attentive listener and put even well-known compositions “into a new light”. Have fun exploring them!

Stay tuned!

On the contrary, in a music recordings store we experience at once a total predominance of pop, rock, hip-hop and dance music, maybe some jazz and world music, presenting most new recordings on CDs and DVDs, but when we take a look at the classics department, what we spot are the names of star instrumentalists and conductors performing music from the past. Why?

On the contrary, in a music recordings store we experience at once a total predominance of pop, rock, hip-hop and dance music, maybe some jazz and world music, presenting most new recordings on CDs and DVDs, but when we take a look at the classics department, what we spot are the names of star instrumentalists and conductors performing music from the past. Why? by Shostakovich or ballets by Stravinsky have indeed much more in common, for example, “Pierrot lunaire” by Schoenberg, written almost in the same year than Stravinsky’s most famous masterpiece “The Rite of Spring.” Of course, there are some or even many similarities between the musical language of the latter two in form, rhythm and colors, but aren’t there also many between, say, tunas and dolphins? Still, they follow very different paths of evolution, and one is fish while the other mammals – a different paradigm of life forms.

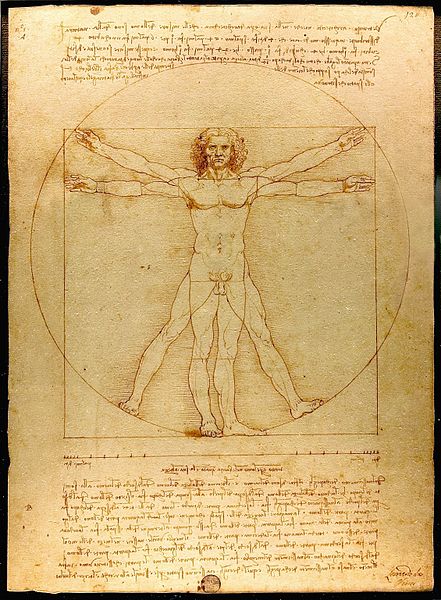

by Shostakovich or ballets by Stravinsky have indeed much more in common, for example, “Pierrot lunaire” by Schoenberg, written almost in the same year than Stravinsky’s most famous masterpiece “The Rite of Spring.” Of course, there are some or even many similarities between the musical language of the latter two in form, rhythm and colors, but aren’t there also many between, say, tunas and dolphins? Still, they follow very different paths of evolution, and one is fish while the other mammals – a different paradigm of life forms. complex rhythms, colors, semantics, dynamics or articulations can be found in other kinds of art – painting, film, poetry, sculpture, etc., only the relationships of pitches are exclusive to music and in their complexity not translatable to other arts. For a better understanding, it must be mentioned that pitches shouldn’t be mixed with the notions of altitude and height in architecture, which have rather a symbolical meaning and belong to semantics.

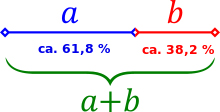

complex rhythms, colors, semantics, dynamics or articulations can be found in other kinds of art – painting, film, poetry, sculpture, etc., only the relationships of pitches are exclusive to music and in their complexity not translatable to other arts. For a better understanding, it must be mentioned that pitches shouldn’t be mixed with the notions of altitude and height in architecture, which have rather a symbolical meaning and belong to semantics. structure of any work of art. The first of them is the golden ratio, a proportion between two parts where the smaller one relates to the bigger as does the bigger to the whole (to the sum of both parts). In a very rough approximation this relation is 1:2 (more precisely 1:1,618).

structure of any work of art. The first of them is the golden ratio, a proportion between two parts where the smaller one relates to the bigger as does the bigger to the whole (to the sum of both parts). In a very rough approximation this relation is 1:2 (more precisely 1:1,618). As the parts in the golden ratio are not equal, it promotes hierarchical functional relations between sounds and chords.

As the parts in the golden ratio are not equal, it promotes hierarchical functional relations between sounds and chords. As far as I can tell, ALL western musical tradition is built on the harmony of the golden symmetry. With some certainty, it applies to the whole Indo-European tradition going back to several millennia! Concretely, it can be recognized at the preference of relations that can be traced back to the overtone sequence, one of the main notions in acoustic studies.

As far as I can tell, ALL western musical tradition is built on the harmony of the golden symmetry. With some certainty, it applies to the whole Indo-European tradition going back to several millennia! Concretely, it can be recognized at the preference of relations that can be traced back to the overtone sequence, one of the main notions in acoustic studies. Every musical tone has a fundamental frequency and many so-called overtones or partials which are higher frequencies resulting from the vibrations of smaller parts of the string or the air mass in a wind or brass instrument. An example of such a ratio can be a subdivision of a string into two, three, four, five, six, etc. equal parts by pressing the string at exactly that point, after what the shorter part of the string would sound, respectively, an octave, a fifth, a quarter, a major third, a minor third, etc. higher from each other.

Every musical tone has a fundamental frequency and many so-called overtones or partials which are higher frequencies resulting from the vibrations of smaller parts of the string or the air mass in a wind or brass instrument. An example of such a ratio can be a subdivision of a string into two, three, four, five, six, etc. equal parts by pressing the string at exactly that point, after what the shorter part of the string would sound, respectively, an octave, a fifth, a quarter, a major third, a minor third, etc. higher from each other. of music harmony (especially in polyphony, the multi-voice tradition) is constantly moving towards more complexity of relations and, at the last stage, to even distorting or layering of more simple structures. Good examples thereof would be the music of Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Britten, Hindemith, Messiaen, or Schnittke. Still, the basic harmonic principle can always be traced back to the symmetry of the golden ratio.

of music harmony (especially in polyphony, the multi-voice tradition) is constantly moving towards more complexity of relations and, at the last stage, to even distorting or layering of more simple structures. Good examples thereof would be the music of Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Britten, Hindemith, Messiaen, or Schnittke. Still, the basic harmonic principle can always be traced back to the symmetry of the golden ratio. The foundation of harmony in avant-garde music is the division of the octave into 12 equal parts: the pitches are organized in such a way that no tone or chord can predominate over the other sounds. The best way to achieve this is to favor intervals of a major seventh and minor second, thus emphasizing the smallest division of the octave into 12 equal parts.

The foundation of harmony in avant-garde music is the division of the octave into 12 equal parts: the pitches are organized in such a way that no tone or chord can predominate over the other sounds. The best way to achieve this is to favor intervals of a major seventh and minor second, thus emphasizing the smallest division of the octave into 12 equal parts. equal parts building the so-called augmented triad, or into six equal parts building the so-called whole tone scale. Both were extensively used in the beginning of the 20th century, also in the classical tradition as an element of estrangement. Still, for the build-up of thirds, typical in the classical tradition, these scales and chords could be easily integrated into the context based on the golden symmetry. In avant-garde music, the ambiguity of the augmented triad and the whole tone scale were frowned upon and generally avoided.

equal parts building the so-called augmented triad, or into six equal parts building the so-called whole tone scale. Both were extensively used in the beginning of the 20th century, also in the classical tradition as an element of estrangement. Still, for the build-up of thirds, typical in the classical tradition, these scales and chords could be easily integrated into the context based on the golden symmetry. In avant-garde music, the ambiguity of the augmented triad and the whole tone scale were frowned upon and generally avoided. Speaking of other musical parameters, I would like to point out that the periodical symmetry has always dominated the rhythms but not the note values, which have shown, in particular with the evolution of triplets, quartuplets, quintuplets and so on, a clear affinity with the golden ratio.

Speaking of other musical parameters, I would like to point out that the periodical symmetry has always dominated the rhythms but not the note values, which have shown, in particular with the evolution of triplets, quartuplets, quintuplets and so on, a clear affinity with the golden ratio. world, especially as part of festivals dedicated exclusively to this new musical art. Still, it has difficulties to be accepted by the audience of classical music in a traditional concert environment.

world, especially as part of festivals dedicated exclusively to this new musical art. Still, it has difficulties to be accepted by the audience of classical music in a traditional concert environment.